The Prime Minister’s Science Media Communication Prize 2014

Batman superhero turned Nanogirl wins Prime Minister’s praise

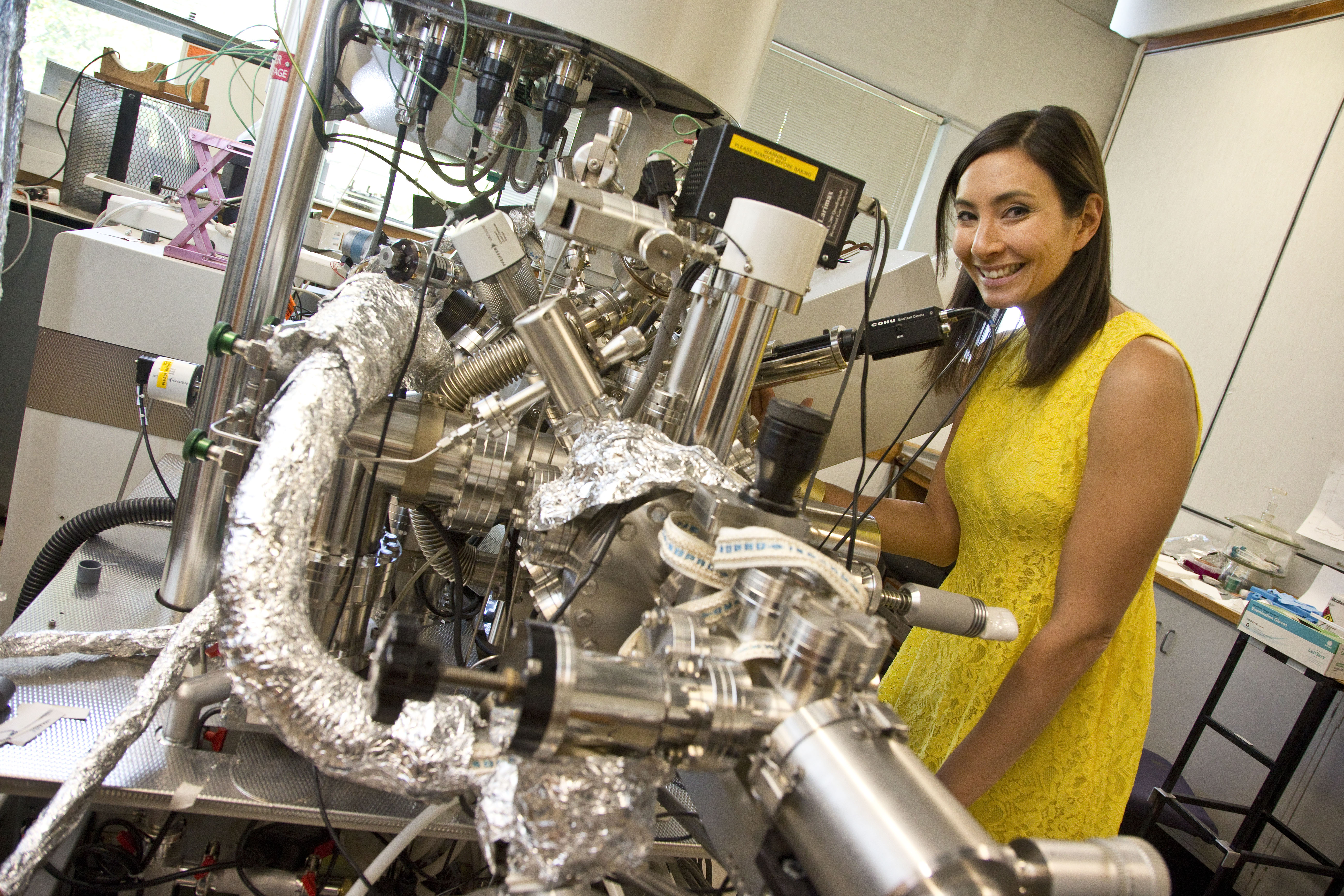

Doctor Michelle Dickinson fell in love with New Zealand during frequent holidays here and liked the country and its growing technology opportunities so much that she decided to stay permanently. The biomedical and materials engineer has today won the 2014 Prime Minister’s Science Communication Prize.

Michelle set up and runs Australasia’s only nanomechanical testing laboratory at the University of Auckland where she is also a senior lecturer. Her research involves building new ways to test tiny, nano-sized materials for the high tech industry and biomaterials to help understand how disease can affect biological cells and tissues.

The prize, valued at $100,000, recognises Michelle’s work to make the serious subject of science fun and accessible, which she does through regular radio and television appearances, tweets, blogs and her ‘Nanogirl’ cartoon persona (www.medickinson.com and @medickinson) .

She recently completed a project which involved carrying out a daily science experiment with a member of the public for 100 days and has established a charity which provides technology-filled days for disadvantaged kids to learn computer coding, 3D printing and robotics.

“I always wanted to be a superhero, just like all kids do, except I never grew out of it. I saw Batman as a mere mortal using his brain to invent things and I naively thought that I had the potential to do that too,” says Michelle.

“Children adore Nanogirl because she’s their science superhero. It helps me show that science does not need to be confined to the classroom or textbooks, and it doesn’t need to be boring.”

While other kids had teddy bears and dolls, Michelle grew up playing with circuit boards and soldering irons and learning computer code and programming.

“My parents said I was always breaking stuff but I called it taking things apart and learning,” she says.

Michelle is particularly focused on inspiring females to push the boundaries of science and resist market-place stereotyping of blue-for-boys, pink-for-girls which, she says, limits children’s potential.

“I see it as a public responsibility to encourage children to continue their scientific education to help New Zealand grow a strong technical skill base.

“It is important for scientists to open the doors on what they do and explain it simply so people are not intimidated by its complexity. As academics, we can sit in our offices and write scientific papers – that’s a safe place to be. But to publicly express a scientific opinion, even when it is backed by scientific evidence, on controversial subjects, such as fluoridation or childhood vaccination, can be a hostile environment.”

Michelle describes herself as naturally shy and introverted. She has trained hard to learn new communication skills and taken professional coaching and courses to overcome her fear of public speaking.

“This prize is lovely recognition as the communication work is something I do in my personal time and I often pay for the associated costs. It’s a true honour and hopefully others can be inspired and feel the power to achieve their goals.

“My parents worked hard but, without any formal qualifications, our family was not well off so the prize recognises that anybody, if they work hard enough, can make a big difference,” says the adrenalin junkie who kitesurfs, mountain bikes and snowboards in her spare time. “Be curious about the world around you, follow your dreams and never let stereotypes scare you.”

The prize money will go towards developing a Kiwi science recipe book using common house-hold ingredients to encourage parents to do science with their children at home, creating a television and Internet science superhero series and producing a popular scientific book giving humorous academic research advice.